Owl-ch! – How a Changing Climate Might Affect Mexican Spotted Owls

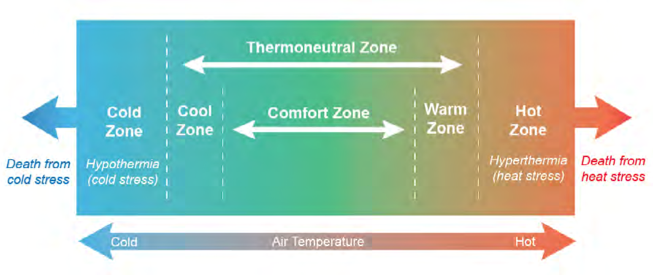

Scientists investigated what might happen to Mexican spotted owls as the air temperature continues to rise in a changing climate. The scientist wanted to know how warmer air temperatures might affect an owl’s individual energy use and the amount of water evaporation an individual owl might experience in the changing conditions.

-

As you have learned in “Owl-ch!,” humans are endotherms who, like other mammals and birds, must maintain a constant internal temperature in changing air temperatures. In this FACTivity, you will...

As you have learned in “Owl-ch!,” humans are endotherms who, like other mammals and birds, must maintain a constant internal temperature in changing air temperatures. In this FACTivity, you will...FACTivity – Owl-ch!

As you have learned in “Owl-ch!,” humans are endotherms who, like other mammals and birds, must maintain a constant internal temperature in changing air temperatures. In this FACTivity, you will...

Glossary

View All Glossary-

Joe Ganey

In a long career in field ecology, I have had so many amazing moments that it is difficult to pick a single highlight. I vividly remember the first time I...View Profile -

James P. Ward

My favorite science experience is difficult to choose—there are so many incredible moments I’ve enjoyed “in the field” studying wildlife and in particular, spotted owls. A clear and memorable high-point...View Profile -

Todd Rawlinson

While studying forest habitats, wildlife species, and wildland fires, we now understand that the greatest risk to most forest species is catastrophic, high-intensity wildfire. During my career, I have learned...View Profile -

Sean Kyle

I have been lucky to work with rodents, birds, bats, reptiles, amphibians, and all the way up to big game across 12 States. I earned a bachelor’s degree in zoology...View Profile -

Ryan Jonnes

The great outdoors has had a lasting impact on my life. The outdoors has shaped my hobbies, work, and family. I like to fish, hunt, camp, and hike. In 2005,...View Profile

Standards addressed in this Article:

Social Studies Standards

- People, Places, and Environments

- Science, Technology, and Society

- Time, Continuity, and Change

Note To Educators

The Forest Service's Mission

The Forest Service’s mission is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. For more than 100 years, our motto has been “caring for the land and serving people.” The Forest Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), recognizes its responsibility to be engaged in efforts to connect youth to nature and to promote the development of science-based conservation education programs and materials nationwide.

What Is the Natural Inquirer?

Natural Inquirer is a science education resource journal to be used by students in grade 6 and up. Natural Inquirer contains articles describing environmental and natural resource research conducted by Forest Service scientists and their cooperators. These scientific journal articles have been reformatted to meet the needs of middle school students. The articles are easy to understand, are aesthetically pleasing to the eye, contain glossaries, and include hands-on activities. The goal of Natural Inquirer is to stimulate critical reading and thinking about scientific inquiry and investigation while teaching about ecology, the natural environment, and natural resources.

-

Meet the Scientists

Introduces students to the scientists who did the research. This section may be used in a discussion about careers in science.

-

What Kinds of Scientist Did This Research?

Introduces students to the scientific disciplines of the scientists who conducted the research.

-

Thinking About Science

Introduces something new about the scientific process, such as a scientific habit of mind or procedures used in scientific studies.

-

Thinking About the Environment

Introduces the environmental topic being addressed in the research.

-

Introduction

Introduces the problem or question that the research addresses.

-

Method

Describes the method the scientists used to collect and analyze their data.

-

Findings & Discussion

Describes the results of the analysis. Addresses the findings and places them into the context of the original problem or question.

-

Reflection Section

Presents questions aimed at stimulating critical thinking about what has been read or predicting what might be presented in the next section. These questions are placed at the end of each of the main article sections.

-

Number Crunches

Presents an easy math problem related to the research.

-

Glossary

Defines potentially new scientific or other terms to students. The first occurrence of a glossary word is bold in the text.

-

Citation

Gives the original article citation with an internet link to the original article.

-

FACTivity

Presents a hands-on activity that emphasizes something presented in the article.

Science Education Standards

You will find a listing of education standards which are addressed by each article at the back of each publication and on our website.

We Welcome Feedback

-

Contact

Jessica Nickelsen

Director, Natural Inquirer program -

Email