Logjams and Beaver Dams: How Different Landforms Affect the Amount of Carbon in an Ecosystem

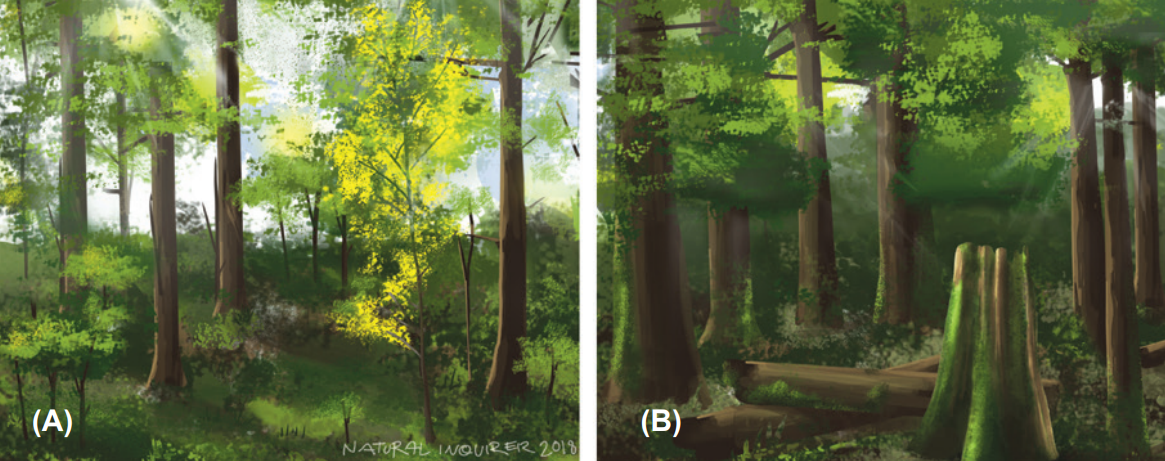

Scientists know little about the movement of litter and dead wood from forests to rivers in mountainous temperate ecosystems. Studying this movement is one way that scientists can better understand the carbon cycle.

The scientists in this study asked three questions about mountainous temperate forest and river ecosystems: (1) Where is carbon found in these ecosystems? (2) How do the landforms beside rivers affect how much carbon is stored in or moved out of these ecosystems? (3) What natural processes affect the location and amount of carbon in these ecosystems?

-

In this FACTivity, you will build a physical representation, or a model, of a beaver dam. Some of the questions you will answer in this FACTivity are: How can you...

In this FACTivity, you will build a physical representation, or a model, of a beaver dam. Some of the questions you will answer in this FACTivity are: How can you...FACTivity – Logjams and Beaver Dams

In this FACTivity, you will build a physical representation, or a model, of a beaver dam. Some of the questions you will answer in this FACTivity are: How can you...

Glossary

View All Glossary-

Ellen Wohl

My favorite science experience was hiking into a remote area of the Nepalese Himalaya to look for flood deposits. Few outsiders had ever visited the area. The local people were...View Profile -

Nicholas Sutfin

One of my favorite science experiences was taking a whitewater rafting trip with other scientists. We rafted on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho’s Frank Church—River of...View Profile -

Roberto Bazan

My favorite science experience was when I was with a crew studying the vegetation in Beaver Creek Meadow in Rocky Mountain National Park. The wildlife we saw and experienced made...View Profile -

Kate Dwire

One of my favorite science experiences has been exploring fens in the Rocky Mountains. Fens are special wetlands that have developed over thousands of years through the accumulation of peat...View Profile

Standards addressed in this Article:

Next Generation Science Standards

- ESS2.C-M1Water continually cycles among land, ocean, and atmosphere via transpiration, evaporation, condensation and crystallization, and precipitation, as well as downhill flows on land.

- ESS2.C-M5Water’s movements—both on the land and underground—cause weathering and erosion, which change the land’s surface features and create underground formations.

- LS2.A-M4Similarly, predatory interactions may reduce the number of organisms or eliminate whole populations of organisms. Mutually beneficial interactions, in contrast, may become so interdependent that each organism requires the other for survival. Although the species involved in these competitive, predatory, and mutually beneficial interactions vary across ecosystems, the patterns of interactions of organisms with their environments, both living and nonliving, are shared.

- LS2.B-M1Food webs are models that demonstrate how matter and energy are transferred between producers, consumers, and decomposers as the three groups interact within an ecosystem. Transfers of matter into and out of the physical environment occur at every level. Decomposers recycle nutrients from dead plant or animal matter back to the soil in terrestrial environments or to the water in aquatic environments. The atoms that make up the organisms in an ecosystem are cycled repeatedly between the living and nonliving parts of the ecosystem.

- LS2.C-M1Ecosystems are dynamic in nature; their characteristics can vary over time. Disruptions to any physical or biological component of an ecosystem can lead to shifts in all its populations.

- LS4.D-M1Changes in biodiversity can influence humans’ resources, such as food, energy, and medicines, as well as ecosystem services that humans rely on—for example, water purification and recycling.

Social Studies Standards

- People, Places, and Environments

- Time, Continuity, and Change

Note To Educators

The Forest Service's Mission

The Forest Service’s mission is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. For more than 100 years, our motto has been “caring for the land and serving people.” The Forest Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), recognizes its responsibility to be engaged in efforts to connect youth to nature and to promote the development of science-based conservation education programs and materials nationwide.

What Is the Natural Inquirer?

Natural Inquirer is a science education resource journal to be used by students in grade 6 and up. Natural Inquirer contains articles describing environmental and natural resource research conducted by Forest Service scientists and their cooperators. These scientific journal articles have been reformatted to meet the needs of middle school students. The articles are easy to understand, are aesthetically pleasing to the eye, contain glossaries, and include hands-on activities. The goal of Natural Inquirer is to stimulate critical reading and thinking about scientific inquiry and investigation while teaching about ecology, the natural environment, and natural resources.

-

Meet the Scientists

Introduces students to the scientists who did the research. This section may be used in a discussion about careers in science.

-

What Kinds of Scientist Did This Research?

Introduces students to the scientific disciplines of the scientists who conducted the research.

-

Thinking About Science

Introduces something new about the scientific process, such as a scientific habit of mind or procedures used in scientific studies.

-

Thinking About the Environment

Introduces the environmental topic being addressed in the research.

-

Introduction

Introduces the problem or question that the research addresses.

-

Method

Describes the method the scientists used to collect and analyze their data.

-

Findings & Discussion

Describes the results of the analysis. Addresses the findings and places them into the context of the original problem or question.

-

Reflection Section

Presents questions aimed at stimulating critical thinking about what has been read or predicting what might be presented in the next section. These questions are placed at the end of each of the main article sections.

-

Number Crunches

Presents an easy math problem related to the research.

-

Glossary

Defines potentially new scientific or other terms to students. The first occurrence of a glossary word is bold in the text.

-

Citation

Gives the original article citation with an internet link to the original article.

-

FACTivity

Presents a hands-on activity that emphasizes something presented in the article.

Science Education Standards

You will find a listing of education standards which are addressed by each article at the back of each publication and on our website.

We Welcome Feedback

-

Contact

Jessica Nickelsen

Director, Natural Inquirer program -

Email

Education Files

Project Learning Tree

If you are a trained Project Learning Tree educator, you may use “A Forest

of Many Uses” and “Loving It Too Much” as additional resources.